Meta Invests $10 Billion to Build AI Project Base

Meta plans to build a data center campus in Richland Parish, with renderings showing extensive facilities designed to power the artificial intelligence boom.

Image credit: Meta.

In the quiet, former farmlands of northeastern Louisiana, teams of excavators have already leveled over 2,000 acres (approximately 8,093,729.6 square meters) of red clay soil. This area, located in the rural stretches of Richland Parish, was once a floodplain crisscrossed by meandering tributaries, overgrown with wild reeds, and still inhabited by black bears. A quarter of the local population of 20,000 lives below the poverty line.

Now, Meta, the world’s sixth-largest company by market capitalization, has arrived. The tech giant aims to transform Richland Parish into the base for its grand artificial intelligence vision, a goal that relies heavily on energy supplied by newly built natural gas power plants. The region offers vast expanses of land and proximity to Louisiana’s extensive Haynesville Shale natural gas field.

In December of last year, Meta launched its largest data center construction project to date: a $10 billion campus comprising nine buildings, lined with rows of servers, covering a total area of over 4 million square feet (approximately 372,000 square meters)—larger than Disneyland.

Meta Chairman and CEO Mark Zuckerberg isn’t stopping there. In July, he named the project Hyperion—a data center “supercluster” that could eventually consume as much energy as 4 million households, potentially making it the world’s largest data center initiative. Zuckerberg stated that Hyperion’s footprint would be equivalent to “a significant portion of Manhattan.”

The project is designed for a computational energy demand of 2 gigawatts, with Zuckerberg noting it could eventually expand to 5 gigawatts to train open-source large language models. Meta has lagged in the AI race due to previous failed projects and its costly, yet underperforming, “metaverse” initiative. Now, Zuckerberg is positioning Hyperion and its large-scale construction as a pursuit of “superintelligent” AI, while also offering $250 million compensation packages to attract AI talent and acquiring a 49% stake in Scale AI.

This represents another monumental competition among tech giants in the artificial intelligence arena, with Meta competing against companies like Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and OpenAI.

“We are making these investments because we firmly believe that superintelligent AI will optimize everything we do,” Zuckerberg stated during Meta’s earnings call on July 30. A Meta spokesperson told Fortune that it is currently impossible to specify which business operations the campus will power, as the state of AI technology by the time the campus becomes operational in 2030 remains unknown.

The sheer scale of the project has left locals in this once-tranquil area deeply astonished.

“I think, like many people, my initial reaction upon hearing that such a remote rural area was chosen for this project was a bit of disbelief,” said Justin Clark, pastor of the First Baptist Church in nearby Rayville. “As I learned more about the project’s content and scale, that sense of shock has lingered—it’s truly unbelievable.”

Clark looks forward to welcoming new workers to the area but admits it’s difficult to fully grasp the project’s immense scale. At a recent chamber of commerce banquet, attendees learned that this is the largest construction site in North America: “It’s incredible,” he marveled.

Overall, new data centers built by major tech companies have enormous demands for energy and water. The electricity required just to keep Hyperion’s servers cooled and operational will be twice the power consumption of New Orleans, and this demand is expected to continue rising.

As the AI boom accelerates, speculation abounds regarding how utility companies will meet the soaring power demands of big tech. For Meta (ranked 22nd on the Fortune 500), regional utility Entergy will build three new natural gas turbines with a total capacity of 2.3 gigawatts—the first expansion of such facilities in the region in decades. This move has sparked dual opposition: consumers worry about rising electricity costs, while climate advocates fear it will setback green energy goals.

In the battle for AI dominance, utility companies have become gatekeepers for the hyperscale tech market. They must weigh the benefits of large-scale capital investments for an emerging industry with uncertain prospects against the risks of rising electricity costs and stranded assets (investments that fail to yield expected returns due to technological or market changes) in the coming decades.

State regulators approved Entergy’s plan on August 20, two months ahead of schedule—a decision that could set a precedent for future collaborations between utility companies and big tech on new power plant projects, particularly in rural areas with low land costs.

“This deal could signal to other states the right path for managing and operating data centers,” Louisiana Public Service Commissioner Davante Lewis told Fortune. “It will serve as a test case nationwide. I’ve heard from investors, credit agencies, and other data center players—the outcome of Meta’s deal will likely establish a framework for all similar projects.”

Meta is leveling large tracts of land in Louisiana’s Richland Parish to build its data center campus. Image credit: Meta.

The Hyperion Blueprint

Although the Hyperion project has garnered broad political support locally, it has also united some environmentalists and major oil companies in opposition, with the latter concerned about rising electricity costs for refineries and petrochemical plants.

“We are well aware that the current situation is complex,” Clark noted, highlighting the conflicting local perspectives. “Some residents whose families have lived on this land for generations feel displaced by the project’s development, yet we have no real say in whether the project moves forward.”

The Louisiana Energy Users Group (including Exxon Mobil, Chevron, and Shell) pointed out that the project would increase Entergy’s energy demand in Louisiana by 30%, posing unprecedented financial risks to existing utility customers.

Despite the controversy, Entergy (ranked 355th on the Fortune 500) has now received formal approval from the state’s Public Service Commission (PSC) to proceed with the natural gas power plant construction. The PSC, a five-member elected body that oversees the state’s utilities, saw Lewis as the sole dissenting vote. The hearing also raised unresolved questions nationwide: How much energy is enough? Can states afford to turn down large-scale economic development investments? And, given that China’s DeepSeek has demonstrated AI technology achieving higher efficiency at lower costs, is the current “frenzy” for energy potentially built on a bubble?

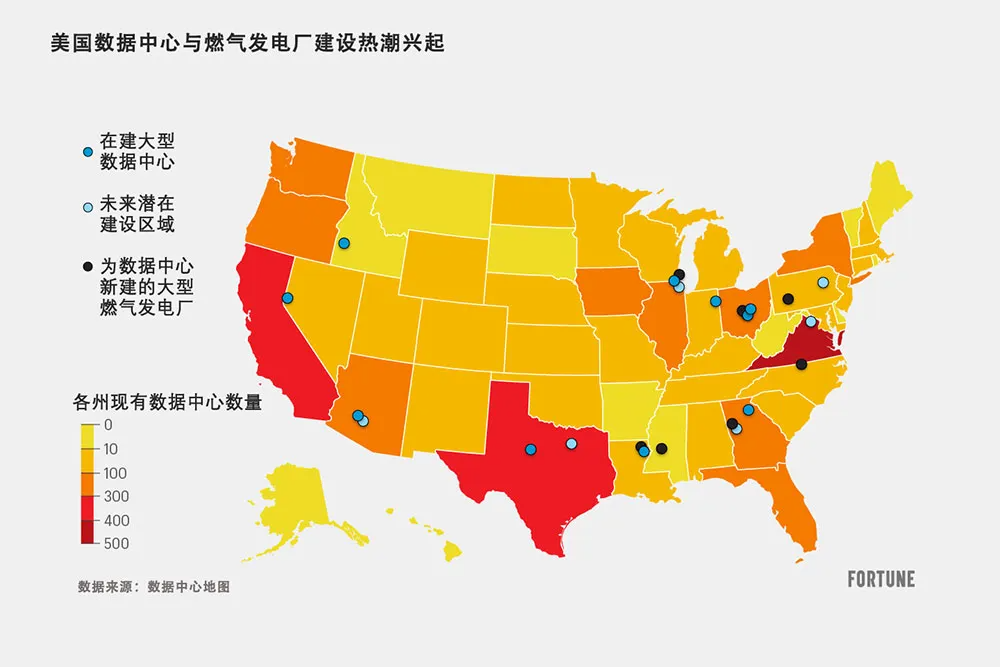

The U.S. currently has about 3,800 data centers (most built during the early cloud computing boom), with the largest clusters concentrated in Virginia’s so-called “data center alley”—home to 500 data centers with easy access to fiber-optic networks for high-speed data transmission. However, compared to the facilities needed to support AI operations, these data centers are relatively small. This year alone, hyperscale tech companies have announced investments of hundreds of billions of dollars to meet the growing demands of generative AI.

In 2025, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft each plan to invest $75 billion to $100 billion in data center construction—a scale of investment that would have been unthinkable to any economist just a few years ago. Zuckerberg stated that Meta’s data center budget for this year is approximately $70 billion (a significant jump from $28 billion last year), and with Meta “going all-in” on “superintelligent” AI, this budget is expected to “increase substantially” by 2026.

The demand for new electricity from these projects is staggering. A recent report from the U.S. Department of Energy estimated that by 2028, data center demand on the grid could triple, potentially accounting for up to 12% of the nation’s total electricity consumption. OpenAI’s Stargate project received $100 billion in upfront investment in January for a $500 billion data center campus in Texas, which plans to build over 100 natural gas power plants to supply the campus and other projects—though many of these may never materialize. Even so, industry research firm Enverus predicts that about 46 gigawatts of natural gas power capacity will come online in the next five years, representing a 20% increase in new construction.

Experts agree that there is an urgent need to boost power generation capacity nationwide. The key, according to Cathy Kunkel, an energy analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), is that the exact incremental demand remains unclear.

U.S. electricity demand remained stable over the past 15 years but grew by 3% last year, marking the fifth-highest annual increase this century. Demand is expected to continue rising in the coming years.

Kunkel noted that the plans crafted by Meta and Entergy to meet this demand are “groundbreaking.”

Driven by the Meta project, Entergy’s stock price has hit record highs. Meanwhile, Meta is covering most of the upfront costs for the Richland Parish project.

Under the contract, Meta will bear the electricity costs of the $3.2 billion natural gas power plant for the first 15 years—a longer term than the typical 10-year agreement but shorter than the 25 years critics demanded—while also covering some transmission costs. Additionally, despite opposition from environmental groups, Meta has committed to building 1.5 gigawatts of solar and battery storage facilities in Louisiana.

Lewis stated that such collaboration could signal to the market that this is the “new gold standard.” But for opponents, it’s a warning sign.

“The issue is that this sets a precedent,” Logan Burke of the Alliance for Affordable Energy testified on August 20. “This arrangement binds all of us—the state’s voters and utility customers—to a non-public contract between two corporations.”

Currently, data center and natural gas power plant construction booms are underway in Virginia, Texas, and California, with the trend spreading to other parts of the U.S., including more rural areas.

Risk of Overbuilding or Fear of Shortages?

The project’s massive scale and resource requirements have alarmed some in Louisiana, where the power grid is already fragile.

In May, over 100,000 households in southern Louisiana experienced blackouts due to imbalances in power supply and demand.

“The data center in Richland Parish will be the largest in the world,” said Margie Vicknair-Pray, coordinator of the Sierra Club’s Louisiana chapter. “How do we ensure that blackouts won’t become more frequent? We still don’t fully understand the impact of data centers on land, resources, and local residents.”

Although Meta has made non-binding commitments to build more renewable energy projects, the Louisiana legislature recently passed a new bill classifying natural gas as “green energy”—meaning Zuckerberg and others can count Entergy’s gas turbines as “green energy facilities.”

Natural gas power plants face other challenges: a shortage of manufacturing capacity for gas turbines in the global supply chain, with turbines sold out for the next five years.

Because the state bypassed standard, longer approval processes, Lewis questioned whether Entergy and Meta truly need additional turbines. “Frankly, why are we only focusing on expanding power generation facilities?” he asked, ignoring considerations for grid efficiency and flexibility. He warned that Meta could exit the project early, leaving electricity users to cover cost overruns.

Entergy spokesperson Brandon Scardigli told Fortune: “For now, natural gas power is the lowest-cost, viable option to meet the 24/7 power demands of large data centers like Meta’s.”

Another uncertainty is the expectation for improvements in computational and energy efficiency. Kunkel drew an inevitable conclusion: The energy consumption of these projects will eventually decrease, “either because technology becomes more efficient or because inefficiency leads to bankruptcy.”

This could mean that utility companies and big tech may find themselves having invested heavily in new natural gas power facilities that ultimately become stranded assets nobody needs.

Meta showcases the blue-tinted cold storage facilities inside its data center. Image credit: Meta.

Other Considerations and Site Selection?

As large data centers expand into rural areas across the U.S., Vicknair-Pray questioned their potential impact: How will air and noise pollution affect farmers and ranchers? Especially the enormous water consumption—could it threaten their livelihoods?

“How will water resources be allocated?” she asked. “What if farmers can’t irrigate their crops?”

The non-partisan think tank Energy Innovation recommends that hyperscale tech companies prioritize investments in renewable energy and battery storage, using newly built natural gas power only as backup when necessary.

Mike O’Boyle, senior director of electricity policy at Energy Innovation, believes building too many new gas turbines carries unnecessary risks. “I understand the current industry environment, where both federal and internal pressures advocate ‘building big and fast.'” But he emphasized that cost considerations must be factored in. “We are in a resource-constrained environment where supply falls short of demand, driving up prices.”

Aside from Virginia, data centers are currently concentrated in populous states like Texas and California. But for developers, one major attraction of data centers is the industrial development opportunities they bring to economically disadvantaged areas like Richland Parish, far from ports and airports.

Adam Robinson, an energy analyst at Enverus, studied the potential directions for future data center construction. He stated that developers consider multiple factors: the price and availability of electricity and land, grid and fiber-optic connectivity, and the time required to connect to the grid.

Robinson predicted that the PJM Interconnection region (stretching from New Jersey through the “Rust Belt” to Illinois) will see significant construction activity. The area attracts hyperscale tech companies due to its competitive electricity market, strong connectivity, and high-speed data transmission capabilities.

He also noted that developers seeking large tracts of cheap land are looking to the western U.S., while server hosting companies and smaller developers are focusing on Texas and the Deep South for low-cost land and tax incentives—for example, Louisiana exempted Meta’s project from sales tax.

Pastor Clark is well aware that technological progress is an unstoppable trend, whether in Richland Parish or anywhere else.

“It’s happening,” he said. “So we hope to make the most of this opportunity.”